Yan Cui

I help clients go faster for less using serverless technologies.

Choreography and Orchestration are two modes of interaction in a microservices architecture.

In orchestration, there is a controller (the ‘orchestrator’) that controls the interaction between services. It dictates the control flow of the business logic and is responsible for making sure that everything happens on cue. This follows the request-response paradigm.

In choreography, every service works independently. There are no hard dependencies between them, and they are loosely coupled only through shared events. Each service listens for events that it’s interested in and does its own thing. This follows the event-driven paradigm.

As always, neither is necessarily better than the other. Depending on the context, one might be more appropriate than the other. And since Lambda itself is inherently event-driven, the choreography approach has become very popular in the serverless community. I’m a huge fan of this approach and have built many event-driven systems using services such as EventBridge, SNS and Kinesis.

However, in this post, I want to talk about when it’s not a good idea and when you should consider the orchestration approach instead.

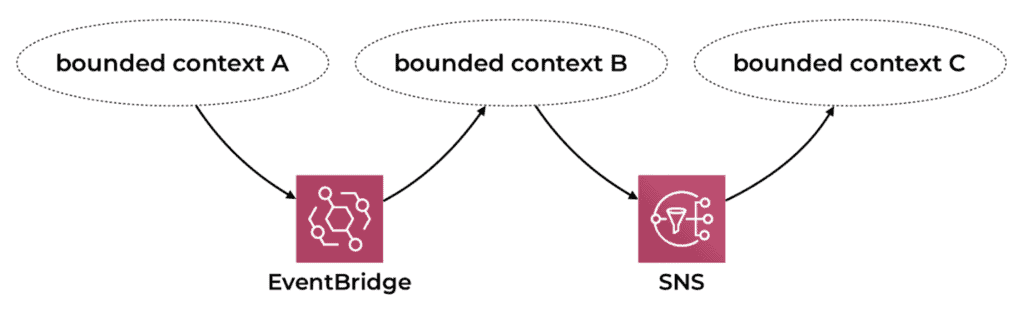

The TL;DR is that, when it comes to implementing workflows, you should prefer orchestration within the bounded context of a microservice, but prefer choreography between bounded contexts.

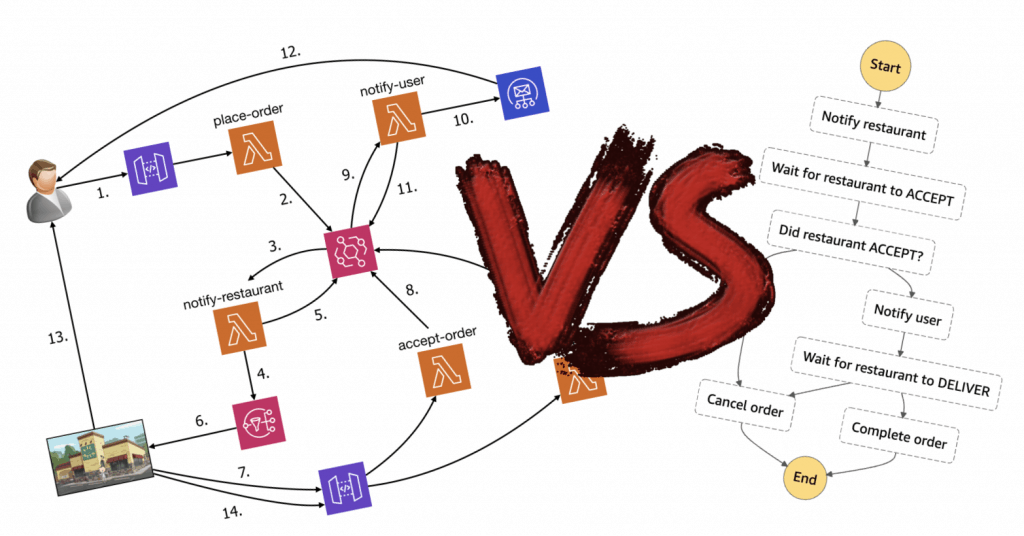

The Choreography approach

Imagine you’re building a food ordering service where customers can order takeaways from their favourite restaurants. A typical order flow might involve the following five steps.

We can model these five steps as events:

order_placedrestaurant_notifiedorder_accepteduser_notifiedorder_completed

With these events, we can implement the order flow using an event-driven approach.

- A customer places an order.

place-orderfunction publishes anorder_placedevent.notify-restaurantfunction is triggered by theorder_placedevent.notify-restaurantfunction sends a message to the restaurant via SNS.notify-restaurantfunction publishes arestaurant_notifiedevent.- The restaurant receives the new order notification in its mobile app.

- The restaurant clicks

Accept Orderin the app, which calls theordersAPI. accept-orderfunction publishes anorder_acceptedevent.notify-userfunction is triggered by theorder_acceptedevent.notify-userfunction sends an order confirmation email to the customer.notify-userfunction publishes auser_notifiedevent.- The customer sees the order confirmation and is eagerly waiting for the food to arrive.

- The restaurant delivers the food to the customer.

- The restaurant clicks the

Complete Orderin the app to confirm order has been delivered. This calls theordersAPI. complete-orderfunction publishes anorder_completedevent.

Every function acted completely independently. None of them had the notion of the overall order flow, they each only cared about:

- What events they are interested in.

- What they should do.

- What events they should publish when they complete their task.

Pros

- Each step of the flow can be changed independently.

- Each step of the flow can be scaled independently.

- No single point of failure.

- Other systems can build on these events – e.g. a

promo-codeservice might be interested in theorder_completedevent and send out discount vouchers to the customer. - The events are useful artefacts on their own, and can be fed into a data lake to generate business intelligence reports.

Cons

- End-to-end monitoring and reporting are difficult.

- Difficult to implement timeouts.

- The order flow is not explicitly modelled and exists only as an emergent property of what system does. As such, it’s only captured in the mental model of someone who understands the system end-to-end.

From a business point-of-view, it also begs the question “are these really separate processes? Or are they different steps within one process?”.

For business-critical workflows like this, wouldn’t you want someone or some team to take ownership of and be responsible for it? When something goes wrong and you lose millions by the hour, do you want a room full of people looking at each other because no-one understands the process end-to-end?

And if there are few people in the company understands how this critical flow works, then it creates an existential risk to the business if these people ever left the company.

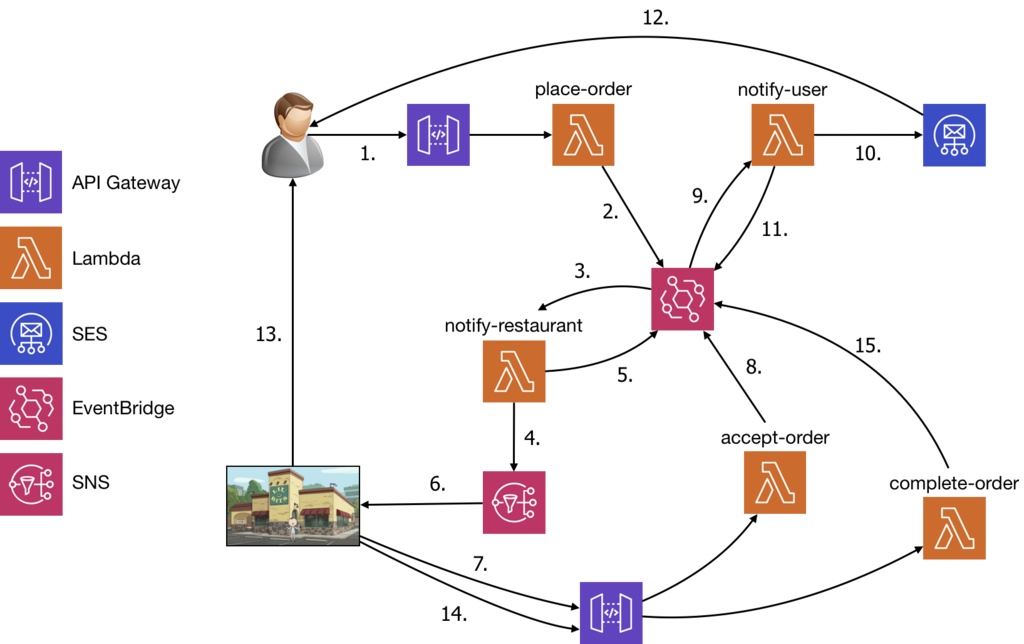

The Orchestration approach

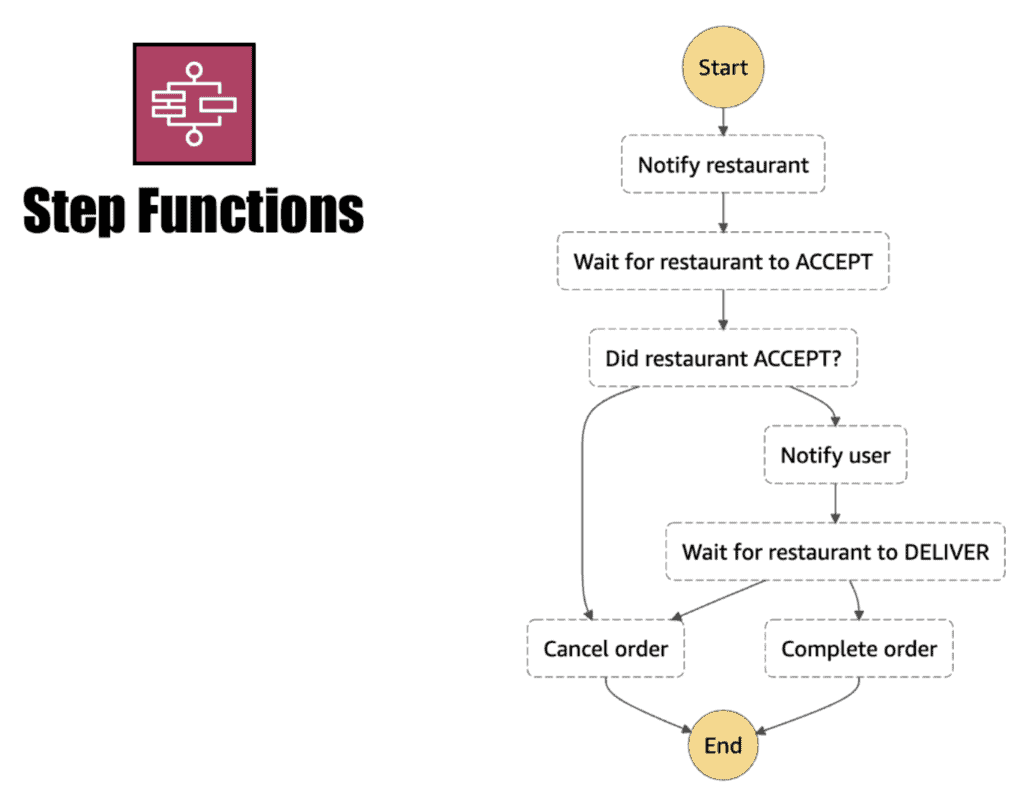

To implement the orchestration approach, I will probably use something like Step Functions and model the order flow as a state machine.

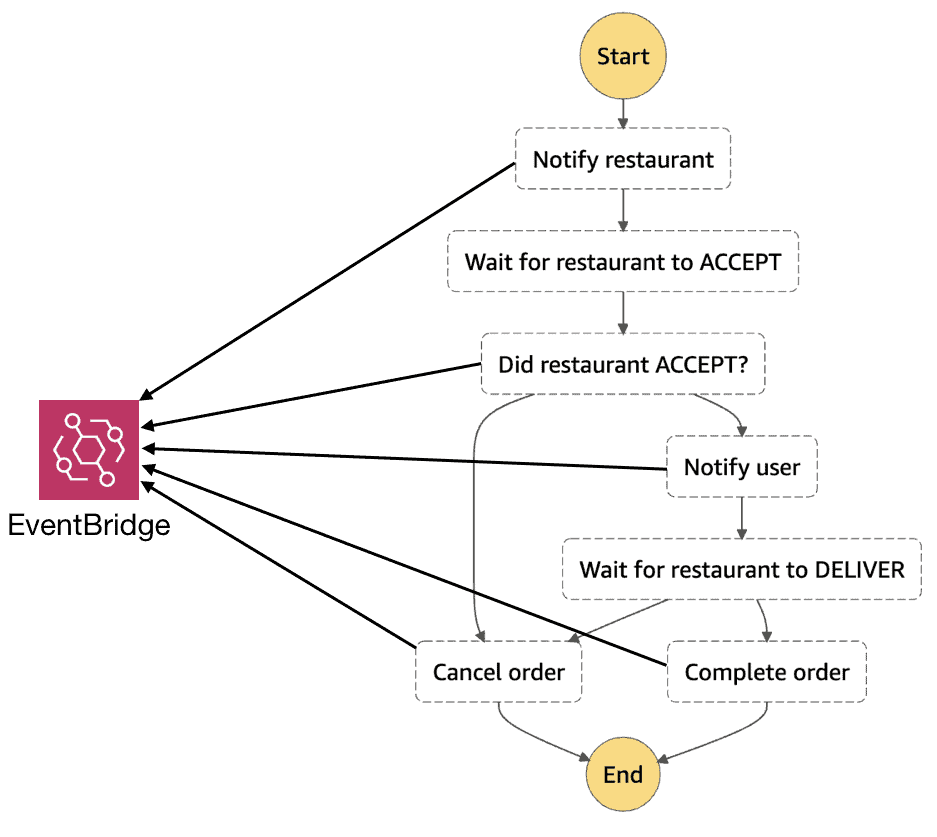

It’s also worth remembering that, although we no longer need to use events to trigger the next step of the order flow, those events are still useful artefacts on their own. So we should publish those same events from Task states in the state machine. For example, after the Notify User state notifies the user via SES, the Task should also publish the user_notified event.

This means we can still decouple the order flow from other business units that wish to build features on top of events related to an order. The aforementioned promo-code service can still rely on the order_completed event as before.

Pros

- End-to-end monitoring and reporting are trivial since Step Functions gives you built-in visualization and audit histories.

- Easy to implement timeout – e.g. for a restaurant to accept an order, or for the total duration of the order.

- Business logic is in one place, and it’s easy to maintain and manage.

- The order flow is modelled and source controlled. You can literally see it in the Step Functions console.

- The order flow is modelled and source controlled. Yes, it’s that important that it should count as two pros!

Cons

- Have to learn yet another AWS service.

- At $25 per million state transitions (which counts

StartandEndby the way), Step Functions is a pricey service. - If Step Functions is down, then no orders can be processed. Although the same might be said about Lambda, EventBridge, or any services that are critical to the working of this order flow.

The hybrid approach

Within a bounded context, I have a specific set of responsibilities that are aligned with a business area. And there are hopefully a small number of components that they can all fit inside my head at the same time. Since they all work together to achieve some specific business capability such as processing payments, they form a highly cohesive unit. And since I own everything within this microservice’s bounded context, I’m free to change and reorganize things so long I don’t break my contract with external services.

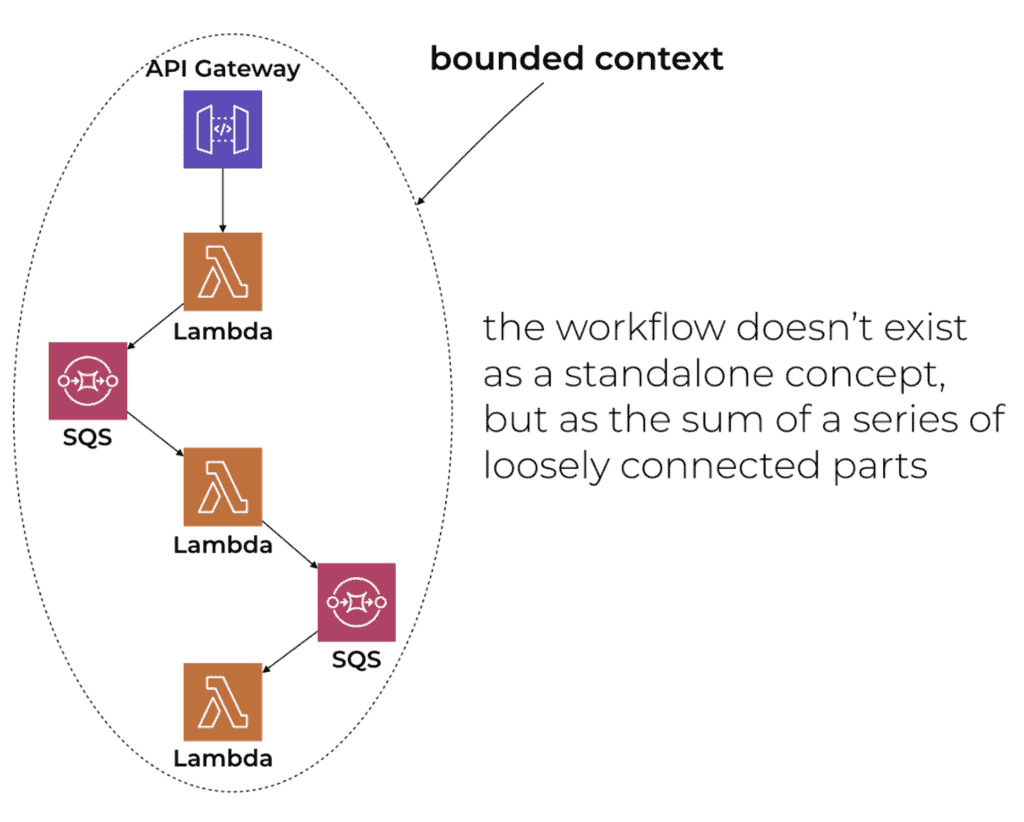

I often see workflows within a bounded context being choreographed through messages in SQS/SNS/EventBridge.

Generally speaking, I think that’s a bad idea.

I love using events to integrate different services together in a loosely-coupled way. But I think it’s a bad idea when it’s done inside the same bounded context because the workflow doesn’t exist as a standalone concept that is explicitly captured and source controlled.

In these choreographed workflows, the workflow only exists as the sum of loosely connected functions. As we discussed above with the food delivery example, this makes them very difficult to reason about and debug. And there’s no easy way to implement even simple things like workflow level timeouts, or even task level tasks for that matter (e.g. timeout the order if the restaurant doesn’t accept or reject the order within 10 minutes).

If this is what you have today, you should consider moving these workflows to Step Functions instead.

But, between bounded contexts, I’ll publish and subscribe to events through SNS/EventBridge/Kinesis, etc. This is so that different parts of the larger system can stay loosely coupled and only build on each other’s events and can evolve and fail independently.

Orchestration and choreography don’t have to be mutually exclusive. Whenever I’m introducing state changes inside a state machine (such as changing the status of an order from pending to processed), I’ll publish those state changes as events. Other services can listen and react to these state changes, and bringing choreography into the picture.

Let me leave you with my rule-of-thumb when it comes to implementing business workflows: use orchestration within the bounded context of a microservice, but use choreography between bounded-contexts.

I hope you’ve found this post useful. If you want to learn more about running serverless in production and what it takes to build production-ready serverless applications then check out my upcoming workshop, Production-Ready Serverless!

In the workshop, I will give you a quick introduction to AWS Lambda and the Serverless framework, and take you through topics such as:

- testing strategies

- how to secure your APIs

- API Gateway best practices

- CI/CD

- configuration management

- security best practices

- event-driven architectures

- how to build observability into serverless applications

and much more!

Whenever you’re ready, here are 3 ways I can help you:

- Production-Ready Serverless: Join 20+ AWS Heroes & Community Builders and 1000+ other students in levelling up your serverless game.

- Consulting: If you want to improve feature velocity, reduce costs, and make your systems more scalable, secure, and resilient, then let’s work together and make it happen.

- Join my FREE Community on Skool, where you can ask for help, share your success stories and hang out with me and other like-minded people without all the negativity from social media.