Yan Cui

I help clients go faster for less using serverless technologies.

After watching Gael’s recent SkillsMatter talk on multithreading I’ve put together some notes from a very educational talk:

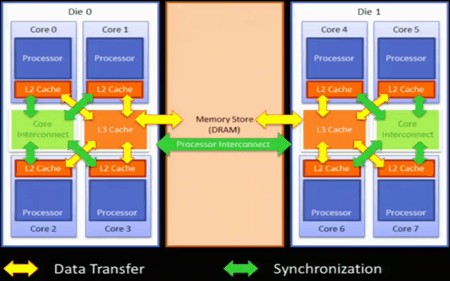

Hardware Cache Hierarchy

Four levels of cache

- L1 (per core) – typically used for instructions

- L2 (per core)

- L3 (per die)

- DRAM (all processors)

Data can be cached in multiple caches, and synchronization happens through an asynchronous message bus.

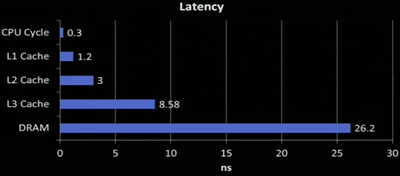

The latency increases as you go down the different levels of cache:

Memory Reordering

Cache operations are in general optimized for performance as opposed to logical behaviour, hence depending on the architecture (x86, AMD, ARM7, etc.) cache loads and store operations can be reordered and executed out-of-order:

To add to this memory reordering behaviour at a hardware level, the CLR can also:

- cache data into register

- reorder

- coalesce writes

The volatile keyword stops the compiler optimizations, that’s all, it does not stop the hardware level optimizations.

This is where memory barrier comes in, to ensure serial access to memory and to force data to be flushed and synchronized across all the local cache, this is done via the Thread.MemoryBarrier method in .Net.

Atomicity

Operations on longs cannot be performed in an atomic way on a 32-bit architecture, it’s possible to get partially modified value.

Interlocked

Interlocks provides the only locking mechanism at hardware level, the .Net framework provides access to these instructions via the Interlocked class.

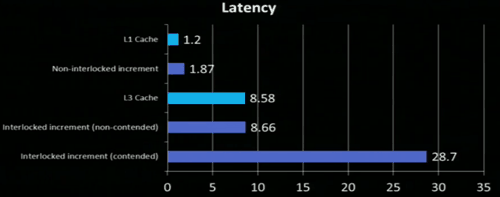

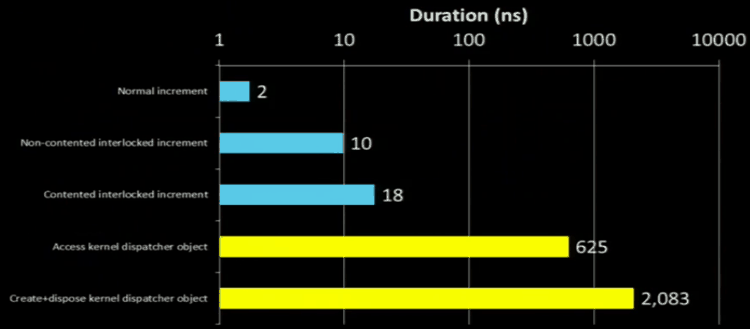

On the Intel architecture, interlocks are typically implemented on the L3 cache, a fact that’s reflected by the latency associated with using Interlocked increments compared with non-interlocked:

CompareExchange is the most important tool when it comes to implemented lock-free algorithms, but since it’s implemented on the L3 cache, in a multi-processor environment it would require one of the processor to take out a global lock, hence why the contented case above takes much longer.

You can analyse the performance of your application at a CPU level using Intel’s vTune Amplifier XE tool.

Multitasking

Threads do not exist at a hardware level, CPU only understands tasks and it has no concept of ‘wait’. Synchronization constructs such as semaphores and mutex are built on top of interlocked operations.

One core can never do more than 1 ‘thing’ at the same time, unless it’s hyper-threaded in which case the core can do something else whilst waiting on some resource to continue executing the original task.

A task runs until interrupted by hardware (I/O interrupt) or OS.

Windows Kernel

A process has:

- private virtual address space

- resources

- at least 1 thread

A thread is:

- a program (sequence of instructions)

- CPU state

- wait dependencies

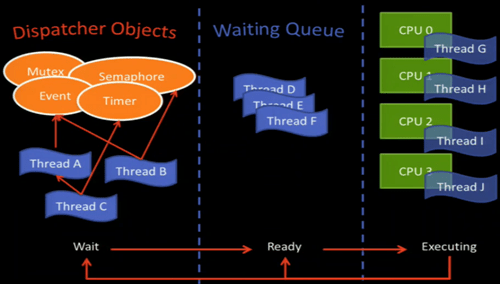

Threads can wait for dispatcher objects (WaitHandle) – Mutex, Semaphore, Event, Timer or another thread, when they’re not waiting for anything they’re placed in the waiting queue by the thread scheduler until it is their turn to be executed on the CPU.

After a thread has been executed for some time, it is then moved back to the waiting queue (via a kernel interrupt) to give some other thread a slice of the available CPU time. Alternatively, if the thread needs to wait for a dispatcher object then it goes back to the waiting state.

Dispatcher objects reside in the kernel and can be shared among different processes, they’re very expensive!

Which is why you don’t want to use kernel objects for waits that are typically very short, instead they’re best used when waiting for something that takes longer to return, e.g. I/O.

Compared to other wait methods (e.g. Thread.Sleep, Thread.Yield, WaitHandle.Wait, etc.) Thread.SpinWait is an odd ball because it’s not a kernel method, it resembles a continuous loop (it keeps ‘spinning’) but it tells a hyper-threaded CPU that it’s ok to do something else. It’s generally useful when you know the interrupt will happen very quickly and hence saving you from an unnecessary context switch. If the interrupt does not happen quickly as expected, the SpinWait will be transformed into a normal thread wait (Thread.Sleep) to avoid wasting CPU cycles.

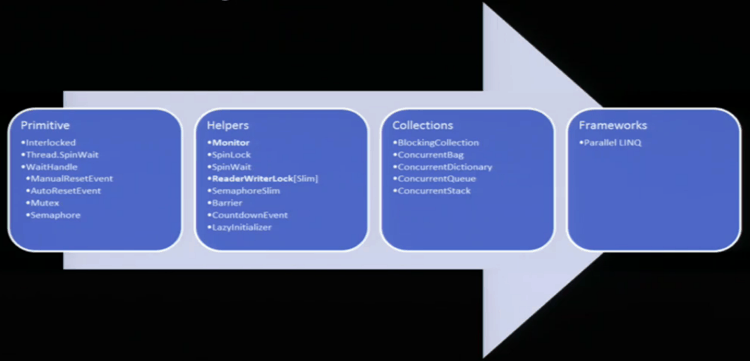

.Net Framework Thread Synchronization

The lock Keyword

- start with interlocked operations (no contention)

- continue with ‘spin wait’

- create kernel event and wait

Good performance if low contention.

Design Patterns

- Thread unsafe

- Actor

- Reader-Writer Synchronized

This is where the PostSharp multithreading toolkit comes to the rescue! It can help you implement each of these patterns automatically, Gael has talked more about the toolkit in this blog post.

Whenever you’re ready, here are 3 ways I can help you:

- Production-Ready Serverless: Join 20+ AWS Heroes & Community Builders and 1000+ other students in levelling up your serverless game. This is your one-stop shop for quickly levelling up your serverless skills.

- I help clients launch product ideas, improve their development processes and upskill their teams. If you’d like to work together, then let’s get in touch.

- Join my community on Discord, ask questions, and join the discussion on all things AWS and Serverless.