Yan Cui

I help clients go faster for less using serverless technologies.

Simplifying things in our daily lives

“Life is complicated… but we use simple abstractions to deal with it.”

– Adrian Cockcroft

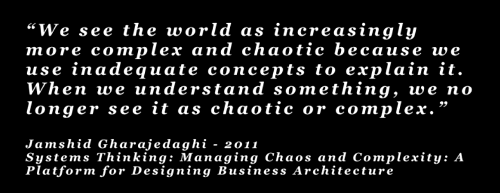

When people say “it’s too complicated”, what they usually mean is “there are too many moving parts and I can’t figure out what it’s going to do next, that I haven’t figured out an internal model for how it works and what it does”.

Which bags the question: “what’s the most complicated thing that you can deal with intuitively?”

Driving, for instance, is one of the most complicated things that we have to do on a regular basis. It combines hand-eye-feet coordination, navigation skills, and ability to react to unforeseeable scenarios that can be life-or-death.

A good example of a simple abstraction is the touch-based interface you find on smart phones and pads. Kids can dissimulate the working of an iPad by experimenting with it, without needing any formal training because they can interact with them and get instant feedback which helps them build the mental model of how things work.

As engineers, we should inspire to build things that can be given to 2 year olds and they can intuitively understand how they operate. This last point reminds me of what Brett Victor has been saying for years, with inspirational talks such as Inventing on Principle and Stop Drawing Dead Fish.

Netflix for instance, has invested much effort in intuition engineering and are building tools to help people get a better intuitive understanding of how their complex, distributed systems are operating at any moment in time.

Another example of how you can take complex things and give them simple descriptions is XKCD’s Thing Explainer, which uses simple words to explain otherwise complex things such as the International Space Station, Nuclear Reactor and Data Centre.

sidebar: wrt to complexities in code, here are two talks that you might also find interesting

Simplifying work

Adrian mentioned Netflix’s slide deck on their culture and values:

[slideshare id=1798664&doc=culture9-090801103430-phpapp02]

Intentional culture is becoming an important thing, and other companies have followed suit, eg.

- Amazon’s 14 principles

- Spotify’s agile culture

- Buffer’s culture of transparency

It conditions people joining the company on what they would expect to see once they’re onboarded, and helps frame & standardise the recruitment process so that everyone knows what a ‘good’ hire looks like.

If you’re creating a startup you can set the culture from the start, don’t wait until you have accidental culture, be intentional and early about what you want to have.

This creates a purpose-driven culture.

Be clear and explicit about the purpose and let people work out how best to implement that purpose.

Purposes are simple statements, whereas setting out all the individual processes you need to ensure people build the right things are much harder, it’s simpler to have a purpose-driven culture and let people self-organise around those purposes.

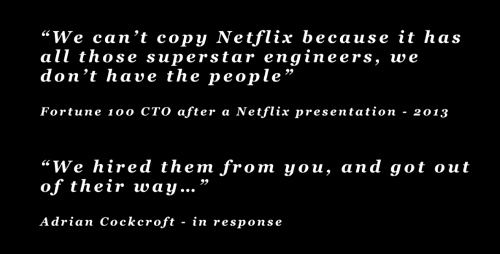

Netflix also found that if you impose processes on people then you drive talents away, which is a big problem. Time and again, Netflix found that people produce a fraction of what they’re capable of producing at other places because they were held back by processes, rules and other things that slow them down.

On Reverse Conway’s Law, Adrian said that you should start with an organisational structure that’s cellular in nature, with clear responsibilities and ownership for a no. of small, co-located teams – high trust & high cohesion within the team, and low trust across the teams.

The morale here is that, if you build a company around a purpose-driven, systems-thinking approach then you are building organisations that are flexible and can evolve as the technology moves on.

The more rules you put in, and the more complex and rigid it gets, then you end up with the opposite.

“You build it, you run it”

– Werner Vogel, Amazon CTO

Simplifying the things we build

First, you should shift your thinking from projects to products, the key difference is that whereas a project has a start and end, a product will continue to evolve for as long as it still serves a purpose. On this point, see also:

“I’m sorry, but there really isn’t any project managers in this new model”

– Adrian Cockcroft

As a result, the overhead & ratio of developers to people doing management, releases & ops has to change.

Second, the most important metric to optimise for is time to value. (see also “beyond features” by Dan North)

“The lead time to someone saying thank you is the only reputation metric that matters”

– Dan North

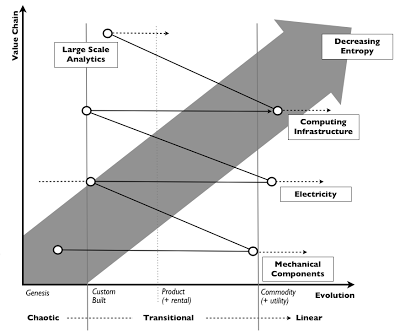

Looking at the customer values and working out how to improve the time-to-value is an interesting challenge. (see Simon Wardley’s value-chain-mapping)

And lastly, and this is a subtle point – optimise for the customers that you want to have rather than the customers you have now. Which is an interesting twist on how we often think about retention and monetisation.

For Netflix, their optimisation is almost always around converting free trials to paying customers, which means they’re always optimising for people who haven’t seen the product before. Interestingly, this feedback loop also has the side-effect of forcing the product to be simple.

On the other hand, if you optimise for power users, then you’re likely to introduce more and more features that contribute towards the product being too complicated for new users. You can potentially build yourself into a corner where you struggle to attract new users and become vulnerable to a new comers into the market with simpler products that new users can understand.

Monolithic apps only look simple from the outside (at the architect diagram level), but if you look under the cover to see your object dependencies then the true scale of their complexities start to become apparent. And they often are complicated because it requires discipline to enforce clear separations.

“If you require constant diligence, then you’re setting everyone up for failure and hurt.”

– Brian Hunter

Microservices enforce separation that makes them less complicated, and make those connectivities between components explicit. They are also better for on-boarding as new joiners don’t have to understand all the interdependencies (inside a monolith) that encompass your entire system to make even small changes.

Each micro-service should have a clear, well-defined set of responsibilities and there’s a cap on the level of complexities they can reach.

sidebar: the best answers I have heard for “how small should a microservice be?” are:

- “one that can be completely rewritten in 2 weeks”

- “what can fit inside an engineer’s head” – which Psychology tells us, isn’t a lot ;-)

Monitoring used to be one of the things that made microservices complicated, but the tooling has caught up in this space and nowadays many vendors (such as NewRelic) offer tools that support this style of architecture out of the box.

Simplifying microservices architecture

If your system is deployed globally, then having the same, automated deployment for every region gives you symmetry. Having this commonality (same AMI, auto-scaling settings, deployment pipeline, etc.) is important, as is automation, because they give you known states in your system that allows you to make assertions.

It’s also important to have systems thinking, try to come up with feedback loops that drive people and machines to do the right thing.

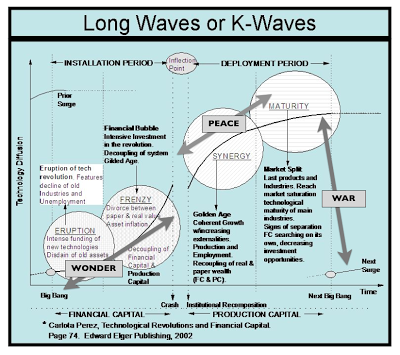

Adrian then referenced Simon Wardley’s post on ecosystems in which he talked about the ILC model, or, a cycle of Innovate, Leverage, and Commoditize.

He touched on Serverless technologies such as AWS Lambda (which we’re using heavily at Yubl). At the moment it’s at the Innovate stage where it’s still a poorly defined concept and even those involved are still working out how best to utilise it.

If AWS Lambda functions are your nano-services, then on the other end of the scale both AWS and Azure are going to release VMs with terabytes of memory to the general public soon – which will have a massive impact on systems such as in-memory graph databases (eg. Neo4j).

When we move to the Leverage stage, the concepts have been clearly defined and terminologies are widely understood. However, the implementations are not yet standardised, and the challenge at this stage is that you can end up with too many choices as new vendors and solutions compete for market share as mainstream adoption gathers pace.

This is where we’re at with container schedulers – Docker Swarm, Kubernetes, Nomad, Mesos, CloudFoundry and whatever else pops up tomorrow.

As the technology matures and people work out the core set of features that matter to them, it’ll start to become a Commodity – this is where we’re at with running containers – where there are multiple compatible implementations that are offered as services.

This new form of commodity then becomes the base for the next wave of innovations by providing a platform that you can build on top of.

Simon Wardley also talked about this as the cycle of War, Wonder and Peace.

Whenever you’re ready, here are 3 ways I can help you:

- Production-Ready Serverless: Join 20+ AWS Heroes & Community Builders and 1000+ other students in levelling up your serverless game. This is your one-stop shop for quickly levelling up your serverless skills.

- I help clients launch product ideas, improve their development processes and upskill their teams. If you’d like to work together, then let’s get in touch.

- Join my community on Discord, ask questions, and join the discussion on all things AWS and Serverless.